ATR and De Havilland facing uncertainty

ATR and De Havilland are the two turboprop manufacturers still in operation. But in this unprecedented period of crisis, one has to wonder what the market outlook is. The ATR aircraft family now has almost 75% of the market share and the ATR 72-600 dominates. For its part, the Dash8-400 is an aircraft which is well suited for high altitude airports and short runways.

But the two manufacturers are now facing a new situation that threatens their survival. In this text, I focus on the elements that play against the two manufacturers.

A different market

The regional aircraft market is very different from that of the main routes. The low volume of passengers leads to a series of important differences: the planes are smaller, the operating costs are higher and the performance metrics s are different. It is for these reasons that most major airlines do not operate their own fleet of regional aircraft. They prefer to entrust its management and operation to companies specializing in this market.

Because they have a lower cruising altitude, turboprops are more suitable for small jumps. The average length of a turboprop flight is between 250 nm and 300 nm, so it takes less than an hour. If we compare, the average flight of a regional jet is double at 600 nm. Over such short distances, fuel consumption is a less important factor in operating costs. On the other hand, the maximum takeoff weight is much more important since a good part of the airport fees are calculated according to the maximum takeoff weight. As a regional plane regularly performs more than six flights a day, this becomes an issue.

The cost of acquiring a regional aircraft is proportionately higher than that of a medium-haul aircraft. In the short term, going for leasing rather than direct ownership reduces the cost of ownership. The proportion of regional aircraft that are leased is 44%. For medium and long-haul aircraft this proportion drops to 25%. Leasing companies therefore have a greater influence on this market.

Dependence on major airlines

The regional aircraft market is the poor member of the airline industry. In order to increase their profitability, the major airlines have not hesitated to twist regional arms for reduction. Over the past decade, major airlines have reported large profits. Meanwhile, regional carriers were lining up to file for bankruptcy in the hopes of restructuring.

It is very difficult for a regional carrier to survive without some sort of alliance with the major airlines. Major airlines buy a predetermined volume of seats at a fixed price. Several regional carriers make 100% of their turnover with a single airline. At best, they have two or three customers but who are stingy in the negotiations anyway. COVID19 will only further weaken regional carriers.

The current situation

The latest regional aircraft usage data provides a glimmer of hope for ATR and De Havilland. While the number of flights worldwide is still below 50%, almost 70% of ATR and Dash8 are in service. De Havilland claims that the regional aircraft market will be the first to recover. But the reality is quite different as the occupancy rate remains anemic. Right now, airlines are adding capacity faster than the passengers rate of growth.

In fact, airlines are rushing to add flights in order to still customers away from others. Each time a company adds capacity, its rivals rush to do the same. In certain regions of the world we are witnessing a strange competition. Large European discount carriers are particularly aggressive at the moment. Jon Ostrower portrayed the current situation on The Air Current as follows: “Airlines are having a knife fight in a life raft.”

By adding more flights now, airlines are only increasing their deficit. At some point common sense will have tom prevail and airlines will stop flying empty planes.

The return to harsh reality

October 2020 is likely to be remembered as “black October” for air travel. Several major airlines are already working on huge layoff programs. Air France, American, Delta, IAG, Lufthansa group, Southwest and United are planning major cuts. It’s a minimum of 100,000 jobs that could be lost this fall.

The current economic situation is forcing airlines to cut across the board. This pressure is inevitably transmitted to aircraft market value from all manufacturers. ATR and De Havilland cannot escape it and their thin order book is more fragile than ever. In addition, pressure from environmentalists will only exacerbate the problem of the two turboprop manufacturers.

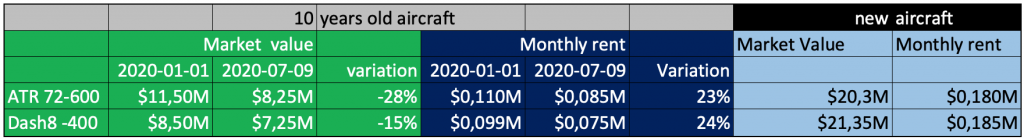

In addition, ATR and De Havilland operate in a market that was mature before COVID19. It will therefore take years to return to the previous level, but this market may not recover. Especially since in Europe the flagskam movement remains vigilant especially for regional flights. At the moment, there is a surplus of good used planes, regardless of the category. Prices are falling, including used regional aircraft of 10 years of age. Here is a table for this purpose:

Source for current market value is Ishka Global

As can be seen, prices have dropped by more than 23% for the ATR 72-600 and the Dash8 400. You have to consider that ATR and De Havilland have very thin profit margins. It was the chronic deficit of the Q400 that forced Bombardier to dispose of it. ATR and De Havilland simply do not have room to maneuver in the face of a depreciated market.

The future

ATR and De Havilland only have old end-of-life aircraft programs. Given the environmental pressures, there is no point in launching a new aircraft program with traditional engines. A new mode of propulsion will be required. There is indeed Pratt & Whitney who works on a hybrid system, but for the moment this project is for re-engines and not new planes.

The future of ATR and De Havilland seems very uncertain to me at the moment, it will require significant state support to survive. Unless an engine manufacturer succeeds in proposing a revolutionary new form of propulsion within two or three years. But there again, public funds will be needed to finance everything.

>>> Follow us on Facebook and Twitter